October 2, 2014

Taste and The Zen of GitHub

There’s a lot of interesting things that happen the first time you really grow a company. Most are exciting, some are challenging, and a few are downright confusing. Every organization (and individual inside) experiences growth differently, which makes for some great stories. This is one of mine.

The only problem with Microsoft is they just have no taste. They have absolutely no taste. And I don’t mean that in a small way, I mean that in a big way, in the sense that they don’t think of original ideas, and they don’t bring much culture into their products.

— Steve Jobs

I’ve always loved this quote. And to be honest, I’m not sure why. It’s an empty statement. What does having no taste mean? How do original ideas and culture factor into taste? Microsoft has always had plenty of original ideas (designers tend to mock and ridicule these especially), and — well — of course they have culture. That’s not a thing you can get rid of. It must be that their original ideas and culture were the wrong type.

What makes Apple have taste and Microsoft have no taste?

About two years ago, GitHub’s product development team was growing fast and I found myself thinking about these questions more and more. We were getting an influx of new points of view, new opinions, new frames of reference for good taste. One thing that challenged me was watching design decisions round out to the path of least resistance. Like a majestic river once carving through the mountains, now encountering the flat valley and melting into a delta.

And the only problem with deltas is they just have no taste.

So how do you build taste?

I’d argue that an organization’s taste is defined by the process and style in which they make design decisions. What features belong in our product? Which prototype feels better? Do we need more iterations, or is this good enough? Are these questions answered by tools? By a process? By a person? Those answers are the essence of taste. In other words, an organization’s taste is the way the organization makes design decisions.

If the decisions are bold, opinionated, and cohesive — we tend to say the organization has taste. But if any of these are missing, we tend to label the entire organization as lacking taste.

Microsoft isn’t lacking taste — they have an overabundance of it.

This is one of the biggest challenges a design leader faces. How do you ensure your team is capable of making bold, opinionated, and cohesive decisions together? It was certainly challenging me. With new employees came different tastes — often clashing against each other, resulting in unproductive debate and unclear results.

We needed some common ground.

Idiomatic code and The Zen of Python

As dynamic languages have become more popular, so have the phrases idiomatic code and good style. With dozens of ways to write each line of code, developers are expected to not only know how to accomplish a task, but in which style they should to accomplish it in.

unless cookies?

if (!cookies?)

if (cookies? == false)

unless !!cookies?

run_away_to_the_woods!There is no Chicago Manual of Style for Ruby. We are instead asked to absorb good style from others who have good style. But who has good style? Matz is nice so we always raise exceptions in unsuccessful calls to methods ending in a bang‽ Unfortunately these kinds of decisions are easy — what isn’t so easy is to know when a class is too big, you’ve chosen poor names, or exactly how much meta-programming is too much. To make it worse, each of these decisions change over time as the taste of the Ruby community evolves. Style guides are often tied to specific organizations and people, not to the Ruby community itself.

Cool.

This may explain why I was overcome with a feeling of jealousy the first time I read The Zen of Python. I’m not usually one to get into religious programming language wars, but by science — I was into this idea. Here’s a taste:

- Beautiful is better than ugly.

- Explicit is better than implicit.

- Simple is better than complex.

- Complex is better than complicated.

- Flat is better than nested.

- Sparse is better than dense.

- Readability counts.

They were answers to why did you do X? And they were shared by, and created for the Python community. And I loved it. (Don’t even get me started about how fantastic the introspectional import this is.)

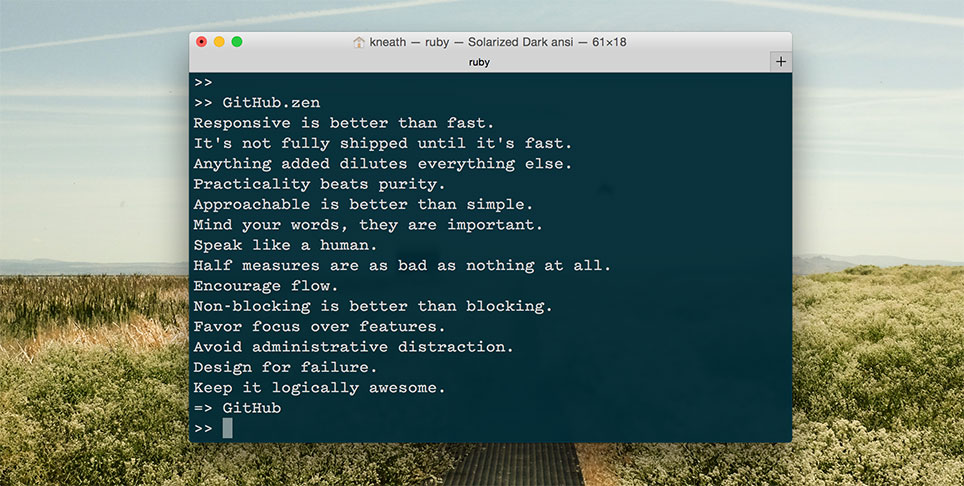

The Zen of GitHub

So I stole the idea. It felt like the perfect medium to communicate taste. I spent about a week writing down ideas and curating a list I was happy with. There was no scientific process to this. Instead, a purposeful effort to distill the thousands of feelings in my gut about building products I’d developed over the years. After writing it down, I asked myself if I really believed in it. The ones I did, I kept, the ones I didn’t, I threw away.

- Responsive is better than fast.

- It’s not fully shipped until it’s fast.

- Anything added dilutes everything else.

- Practicality beats purity.

- Approachable is better than simple.

- Mind your words, they are important.

- Speak like a human.

- Half measures are as bad as nothing at all.

- Encourage flow.

- Non-blocking is better than blocking.

- Favor focus over features.

- Avoid administrative distraction.

- Design for failure.

- Keep it logically awesome.

I presented these in two ways: as part of a presentation given at our semi-annual product development summit (where I elaborated on each point) and as a pull request in our codebase.

Committing the zen to our codebase was important. It made them ours, not mine. It made them malleable, not forever. It made them the responsibility of the whole product development group, not just people who labeled themselves designers.

And most importantly, it was written down. A lot of leaders try to communicate through speeches and meetings, but this is a mistake in fast growing organizations. Written words anchor better in fast moving environments. Written words read the same as they were authored. Written words can be revised, edited, and changed. Written words are the best.

But keep it short — because everything added dilutes everything else.

Onward and inward

MMM. .MMM

MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM

MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM ____________________________

MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM | |

MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM | Keep it logically awesome. |

MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM |_ ________________________|

MMMM::- -:::::::- -::MMMM |/

MM~:~ ~:::::~ ~:~MM

.. MMMMM::. .:::+:::. .::MMMMM ..

.MM::::: ._. :::::MM.

MMMM;:::::;MMMM

-MM MMMMMMM

^ M+ MMMMMMMMM

MMMMMMM MM MM MM

MM MM MM MM

MM MM MM MM

.~~MM~MM~MM~MM~~.

~~~~MM:~MM~~~MM~:MM~~~~

~~~~~~==~==~~~==~==~~~~~~

~~~~~~==~==~==~==~~~~~~

:~==~==~==~==~~

It’s often hard to know how much your words are hitting home as a leader. People always listen, but you’re literally paying them for that privilege. The gap between listening and believing is the hard part.

Which is why it made me so happy to see the zen spread. At first, in small design discussions. Then in our api. And in Hubot zen me. And then in wallpapers for our desktops.

Pretty soon it wasn’t just a presentation I gave or a file I committed. It was The Zen of GitHub. A thing by itself, free to be made fun of and celebrated all at once. And that’s pretty cool.

Design is a hard job. No matter how much we love our work, some will always hate it (and they’ll always let us know). Things change so fast, we’re lucky if what we designed a year ago still exists today. It can be really difficult to be proud of our work.

I’m proud of The Zen of GitHub. I hope it lasts. I hope it changes. And I hope that perhaps, a decade from now, people will think of GitHub as an organization with taste. And perhaps when asked what that means, they’ll have a better answer than original ideas and culture.

If you'd like to keep in touch, I tweet @kneath on Twitter. You're also welcome to send a polite email to kyle@warpspire.com. I don't always get the chance to respond, but email is always the best way to get in touch.

Wallpapers by

Wallpapers by