“So, are you gonna have a swimming pool?”

No, I am not going to build a swimming pool in South Lake Tahoe.

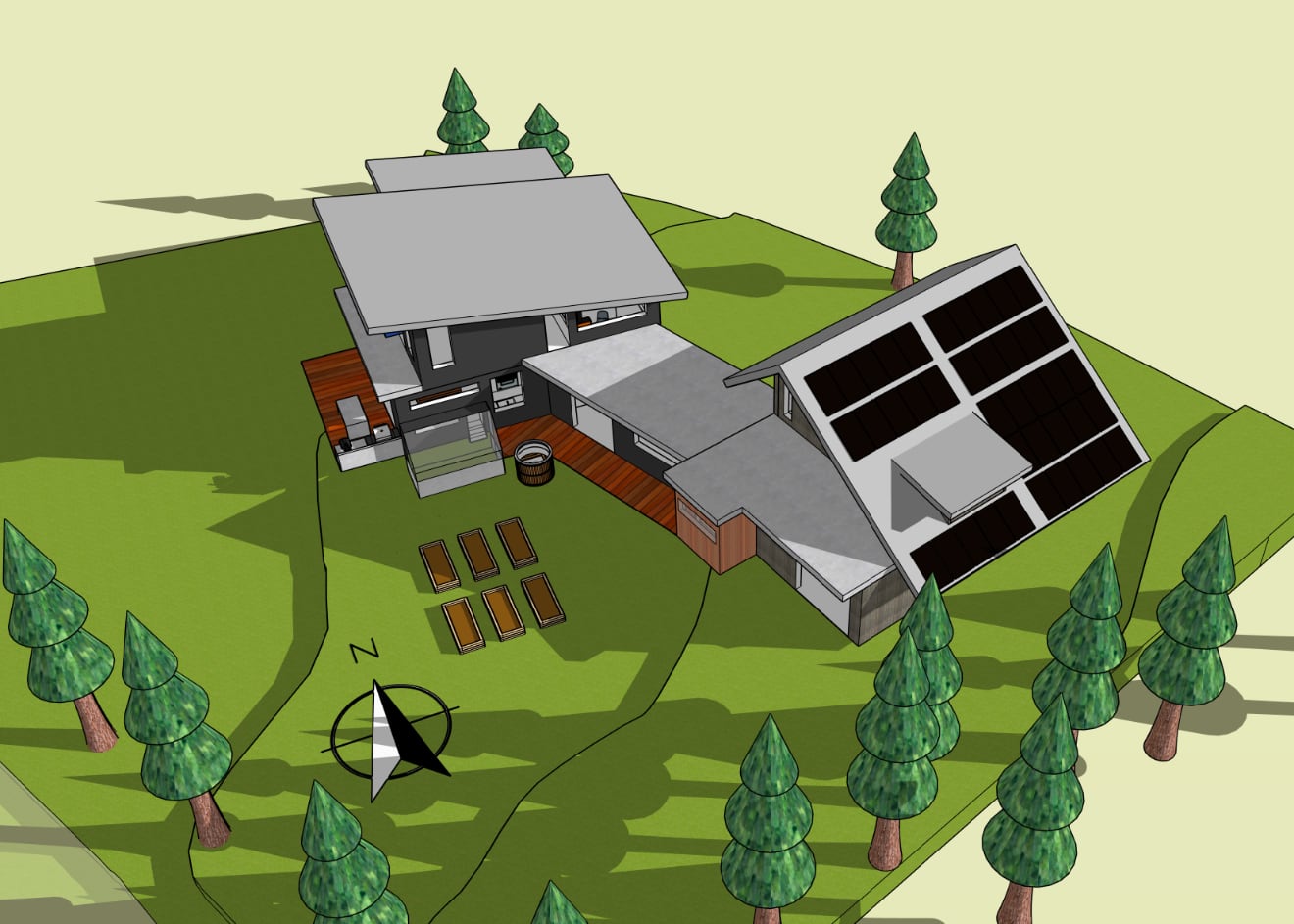

In fairness, the hole in the ground did look suspiciously swimming pool esque. But this hole in the ground was for my basement. A hard won basement that required consultants and backhoes long before any building plans existed. A basement that I’m very excited about! It’ll allow the house to sit slightly proud of the grade, rising above the snow in the winter, protecting the crawlspace from hibernating bears, and presenting a non-ignitable material to burning embers and grass in the summer. And the extra space will afford a root cellar, music room, and mechanical equipment inside the conditioned envelope — all while staying within TRPA’s coverage and height limits.

All of that is to say — I’m building a house! Which is kind of a weird turn of phrase — I won’t be building it. The good folks at Sierra Sustainable are handling that.

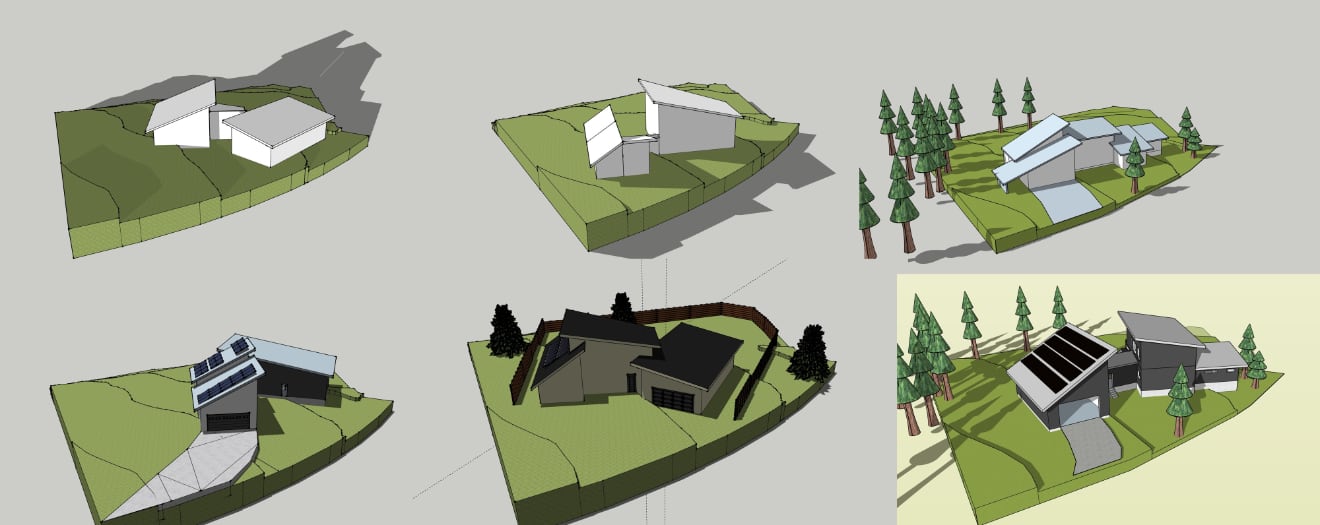

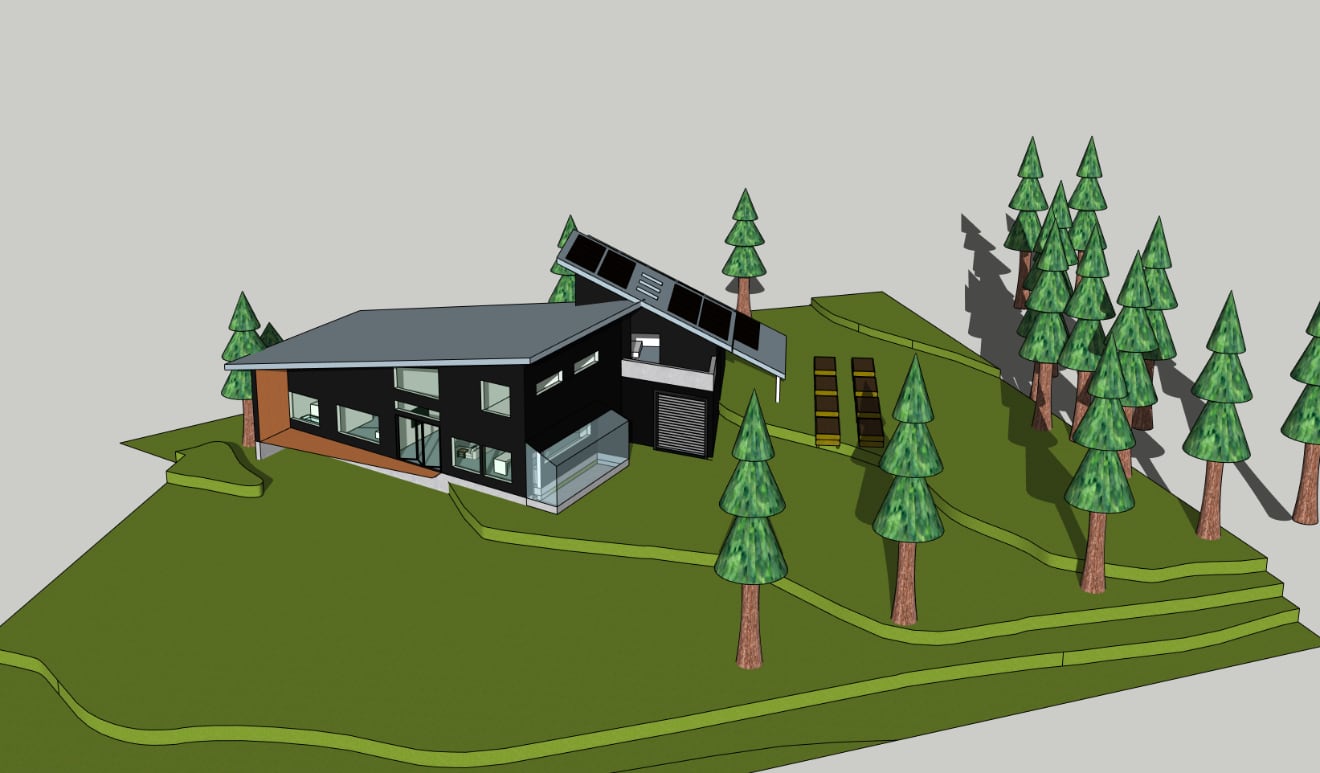

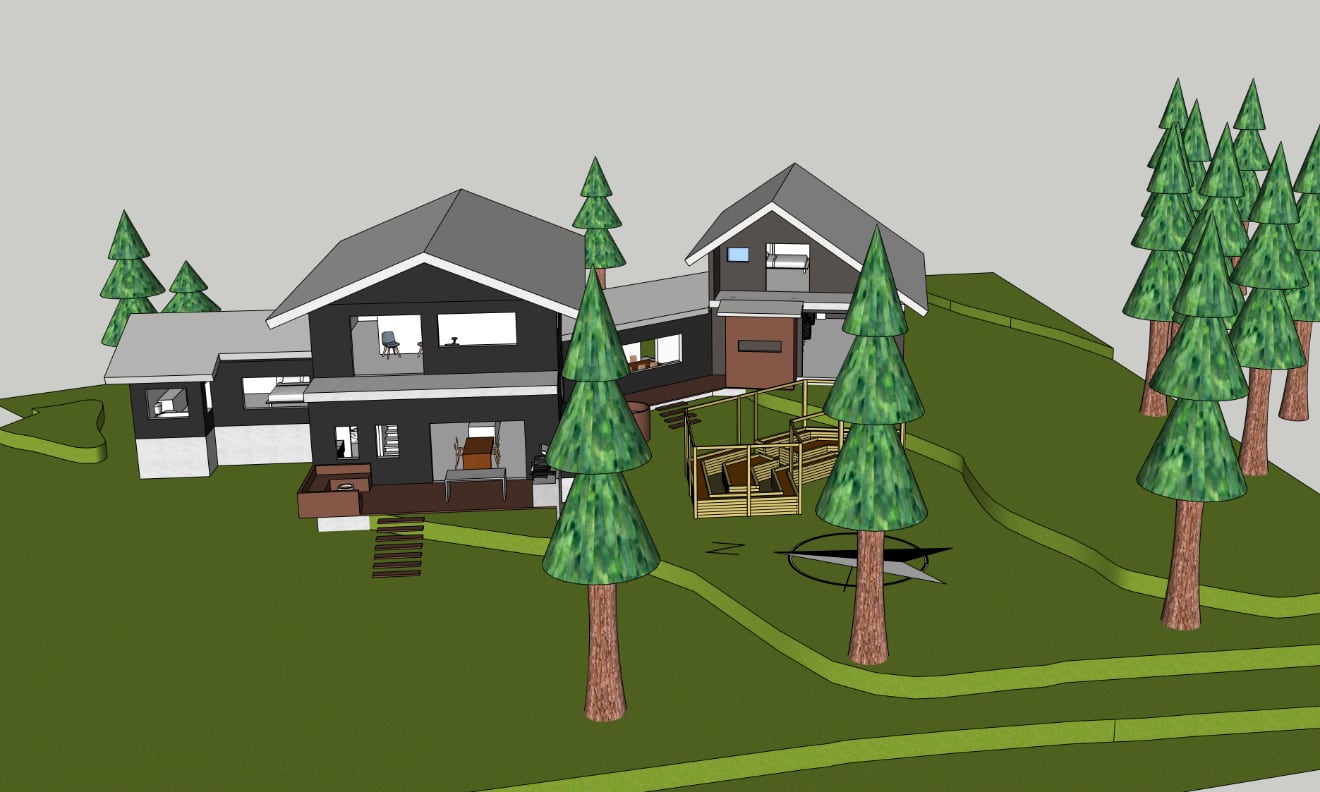

But over the past two and a half years, I’ve been absorbed in designing this house. I’ve sucked up information about architecture, building science, and local regulations — thrown them into dozens of SketchUp models — and my builders have iterated on them and turned it into a set of construction documents.

After a couple years of building department bureaucracy, a megafire burning through town, a historic atmospheric river, a month of record snowfall, and the driest winter on record… it’s starting to become a very real house. My very own money pit!

And you may ask yourself

well, how did I get here?

That house

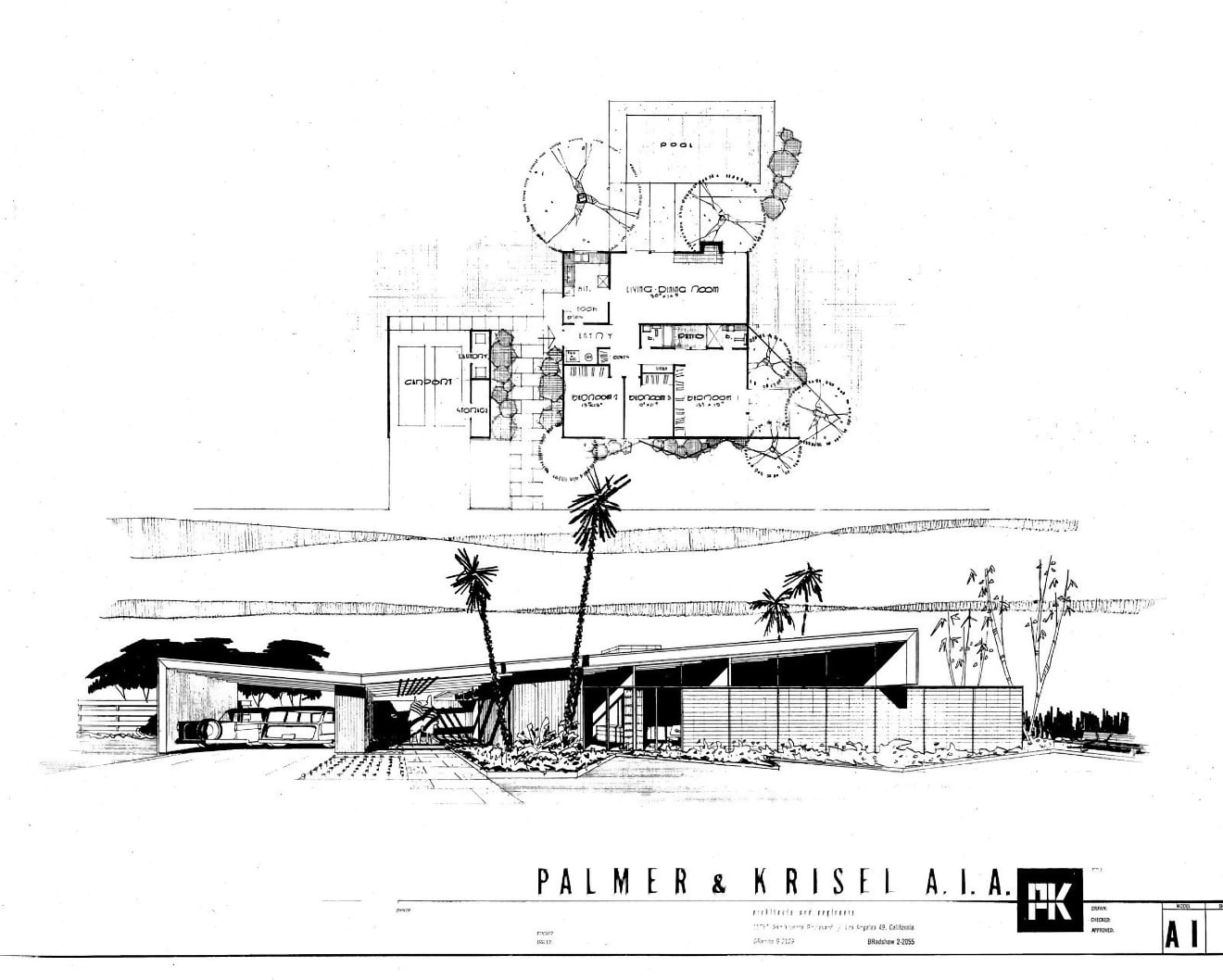

If you spend any time in Tahoe, you’re familiar with that house. It’s the same house with slightly different siding. It pays no attention to the angle of the sun, local weather, the shape of the lot, or the positions of the trees. It is too large and expensive for almost all local working class residents. It is Tyvek-wrapped, forced-air, asphalt-shingle relic of outdated building science, unprepared for the present — let alone the future. Spec builders love it — they pour the same foundation, frame the same walls, install the same plumbing and mechanicals. It’s known. Building departments love it — what’s better than a plan that’s identical to the previous 90 incarnations? You can practically take a nap during plan check.

I hate that house.

But I have to admit it is not an evil house. It is how the vast majority of houses in America are built today. Developers buy large swaths of land, buy a couple of off-the-shelf building plans, and build the exact same house over and over, occasionally letting clients choose siding and interior finishes. It is the bleeding edge of the financialization of shelter.

So what do you do if you don’t want that house? Hire an architect!

I didn’t hire an architect

More so than a beautiful artifact of architecture, I wanted a well built home designed for Tahoe. That made my first priority to find good builders. Ones that embraced modern building science, use quality materials, are familiar with our local weather and regulations, and employ experienced craftsmen.

One day while wandering around a new neighborhood, I spotted a house that wasn’t that house. This house was Lighthaus — a single family residence designed by Peripherie Design and built by Sierra Sustainable Builders. It was the first time I’d seen builders inside the basin building something different.

Later, when touring the house during their completion party, I could see this house was built by people who care. My assumptions were validated by the designer/owner who said something like I wouldn’t even consider working with a different build team in the future. After meeting Cory & Brandon and learning about their passion for well-built homes and their love for South Lake Tahoe, I knew they were the team I wanted to work with.

After acquiring an empty lot and settling on the build team — my next move was to start the bureaucratic struggle with the building department toward a building permit. I know, this probably feels a bit backwards if you’re used to building in Idaho. But this is California — and inside of the Lake Tahoe watershed at that. At the time I closed on the lot (summer of 2019), it was looking like I wouldn’t be able to get a building allocation (roughly, permission to submit building plans) until 2022 due to a forthcoming two year audit. So it was important to start this process early.

In the meantime, I wanted to better understand the limitations and possibilities of what could be built on the lot so I could provide better feedback during design. Tahoe is a unique place to build homes, and the TRPA (Tahoe Regional Planning Association) imposes several restrictions that are unique to the basin — most notably coverage. Coverage is square foot limiting algorithm that encompasses roof overhangs, driveway size, decking material, and foundation footprints. It’s not intuitive or easy to understand, but it is the overriding design constraint for all residential construction.

So I picked up SketchUp, watched a few tutorials, and started sketching out some ideas to explore what was possible.

As I got deeper into this process, I realized that I was really enjoying it. Modeling in SketchUp allowed me to rapidly see the tradeoffs of positioning the driveway in different areas, see how the sun would move through different rooms throughout the days and seasons, how much room I’d have for furniture, what the shape of the yard would look like, how much roof area would be available for solar panels — and all in a model with real measurements that fit within the actual restrictions for our lot.

So, that’s why I didn’t hire an architect. I just really enjoyed designing this house. Despite my civil engineering degree, I’m not anti-architect. In fact I’m working with several for other projects right now! But for this house? My house? I decided to keep doing the thing that brought me joy.

Iteration, iteration, iteration

I’m a big fan of iteration when setting out to create something new. In a perfect universe, I’d build a house, live in it for a while, and re-build it every year for a decade or so. Every iteration of the house would improve upon its predecessor until all the kinks were ironed out, the light hit the walls just so, and every space was perfected for its use. But that’s a fantasy left for science-fiction. In the real world, building a house is a one-shot effort, and that means lots of planning. Every wall, every window, every doorway needs to be carefully designed and engineered long before construction starts. That’s doubly true in today’s world of long lead times (the supply chain and all that). Traditionally, architects have used sketches and drawings to communicate their ideas to their clients during this phase.

These drawings kind of suck. They’re pretty artifacts to look at, but they don’t do a good job of describing how a house will live to someone who isn’t deeply experienced in building structures from drawings. This is why architects also learn how to create physical models made of styrofoam and toothpicks to communicate their ideas.

Unfortunately, we’re not building a school for ants, and these models don’t communicate interior spaces well at all. More importantly, drawings and models aren’t really iterative. They take a long time to produce, and can’t be easily modified. But this is where computers excel! Iterations are cheap, and easy modification is the rule. This is what drew me to 3D modeling — specifically SketchUp. I have to admit I was intimidated — I had never really done any 3D modeling. But the world of 3D modeling has become extremely accessible in the past decade or so. There are many free tools (SketchUp and Blender being most popular), and tons of free training videos available. It only took a few days of dedicated study time to master the basics and start getting value out of my models.

Most importantly, the process was very iterative — I could copy and paste elements from different ideas together, rotate them around, poke windows wherever I pleased, and gain a lot of understanding for how the house would feel with minimal effort.

I love this type of accurately-modeled iteration because it allows you to play with ideas and see tradeoffs in a holistic sense. It’s like using real user data for your digital prototypes instead of nicely formatted cherry-picked sample data. What is the tradeoff of solar production, passive gain, and garden size given different building masses? How much smaller would my kitchen need to be if I were to position the driveway differently?

This is the core of why I love to use iteration on problems with several interconnected variables. You can try to be boy-genius and juggle height restrictions, setbacks, coverage, sun paths, roof pitches, and trees in your head… or you can just try a dozen different ideas and build an intuitive model of the problem over time.

Curious if a solution will work? Try it out.

You don’t even have to be very experienced in SketchUp to get a lot of value out of it. Just having a realistic geo-located sun model is an incredible tool for building houses. Ever wonder how light will move through your open concept living room during the summer solstice? Easy!

In the end, the majority of my time in SketchUp has been used to virtually wander around my house-to-be. To look at the kitchen from different angles, to play with different appliance sizes, and to think about how we’ll live in the space. I’ve definitely become that person wandering around my friend’s houses with a tape measure to better match reality how my 3D model feels. Oh is that island 12ft long? Interesting.

All this casual wandering and time spent with the construction documents has also given me an accidental bonus — I will know this house. I will know where every air duct is, how the floor is built, where the electrical wires go, and why every wall is where it is. As someone who has spent his whole life solving mysteries of old houses, it’ll be kind of nice to live in something that isn’t a mystery.

And yes, if you so choose there are many ways to import your SketchUp models into VR headsets and even-more-virtually wander around your house to be.

Collaboration

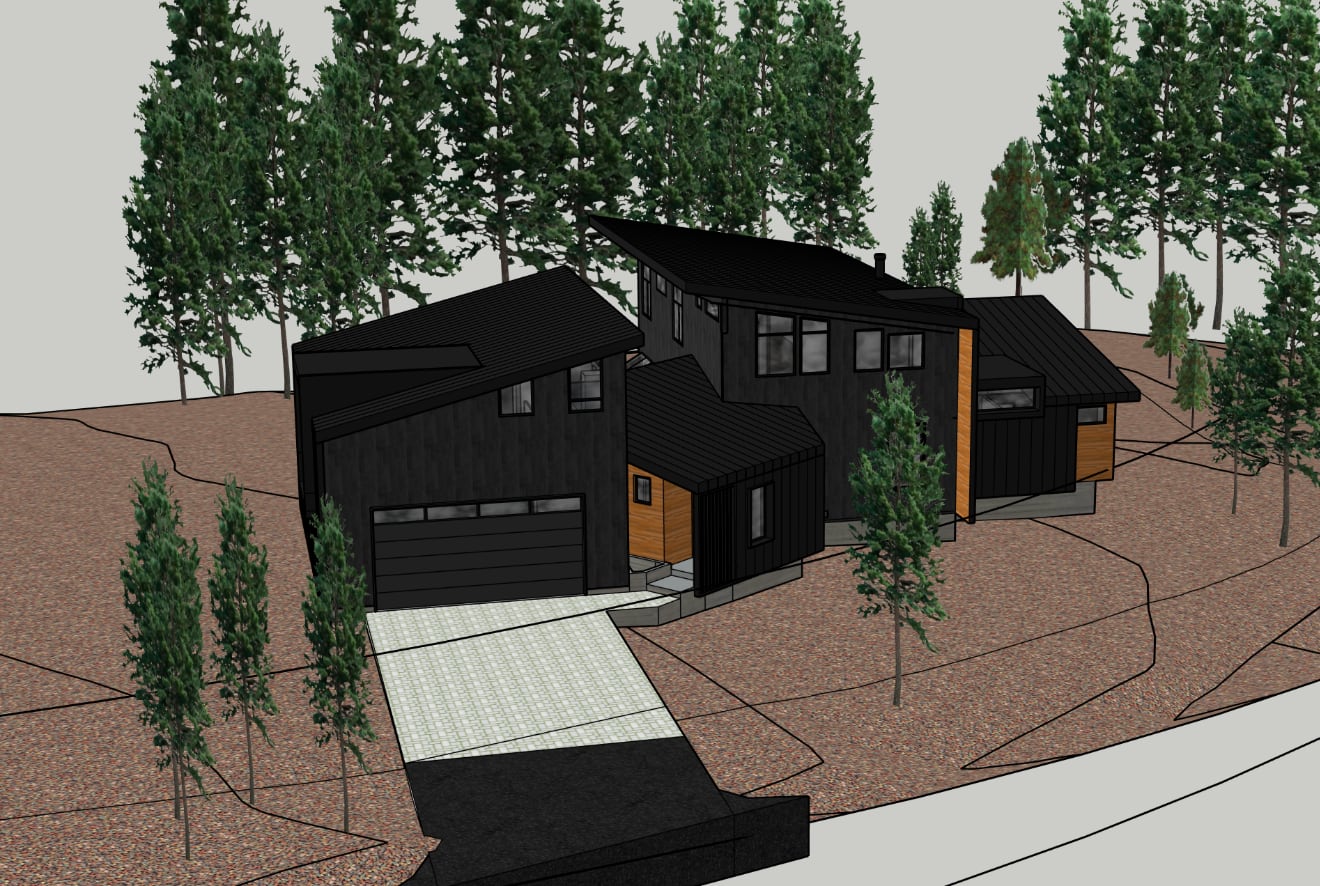

Another huge benefit of iterative tools like software is the collaboration it brings possible. Which was pretty important. Because I am no architect, and I have never designed a house. So it was good to have Brandon from SSB take my models and make something a little more reasonable and buildable.

Because I’d taken the time to learn SketchUp, I could then take his models and iterate on them the same way he’d iterated on mine. And — honestly — this kind of feels like how designing a house should work.

The one-way street of iteration via design reviews feels very outdated now that I’ve worked this way. An architect may be an expert in how to design buildings — but you’ll be living in this house, not the architect. You’ll be able to build a better mental model of how you expect to live in it.

Beyond SketchUp

At this point, the construction documents are done, the foundation has been poured, the windows have been ordered, and the framers are assembling large piles of engineered lumber into a permanent structure. The floor plan won’t be changing.

So my interests have shifted from SketchUp toward more realistic renders to explore materials and lighting. And hoo-boy is there a deep end to fall down that rabbit hole.

The particular deep end I’ve decided to settle on is v•ray. And for as frustrating as rendering can be, the results can sure be pleasing.

With every render, I get a little bit better at understanding what kind of textures provide a result similar to my real-world samples, and just how much detail is needed to really pull off an accurate render.

And I think that pleasing nature is what has kept me busy. Because if I’m honest, at this point I don’t think the renders are helping me that much. I’ve learned through trial and error that rendering is a lot more of an art than a science — so in a lot of ways I’m making pretty pictures, not accurate views of what will be.

All in all, this has been an incredibly fun project to work on. And it’s even more exciting now that the building is starting to take shape in the physical world. Even though I spent five years of college learning to design physical infrastructure, my professional career has revolved around building things in the digital world. And that was fun! But deep in my heart I’ve always been pulled towards building things in the real world — bridges, buildings, roads, and the like. The accessibility of 3D modeling has really helped bridge the gap of speed of iteration (what I loved about working in software) and the realness of physical infrastructure (what I loved about civil engineering).

I’ve also enjoyed the process of getting here. Aside from 3D modeling, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to understand what makes a good home a good home. I’ve learned about a form of architecture that deeply resonates with me, and just how far building science has come in the past few decades.

For better and for worse, this home will be a product of my dreams, born out of my opinions of where our future is headed. It’ll be a bit ridiculous, but in ways that might be confusing to most. I won’t have a 10,000 sqft deck overlooking the lake, but I will have a geothermal heat pump heating the hot tub and windows with excellent air sealing. In fact — the stuff I’m most excited about isn’t how the house looks at all, but rather the way the house will live. How the snow sheds. Why it’ll resist ice dams. How it’ll deal with smoke season. How it’ll resist grid failures. And why, for the first time in my life, my house will have straight walls.

You can be an architect house designer!

If you’re building a commercial building or multi-family residence, you need an architect — someone with a state issued license that allows them to call themselves an architect. Anyone without that license is just a designer. However, I suspect a lot of people don’t realize that anyone can be a designer. In every state in America it’s entirely possible to design your own home without any kind of licenses or certifications. It may go without saying, but your home still has to be engineered and meet all building codes and regulations. And of course — you need to be able to afford it. Half an architect’s job is budgeting.

And well-built modern homes are complicated. Long past are the days of craftsman homes ordered at Sears and delivered as a pile of lumber on a truck. If you’re building a house today, you’ll want a small army of consultants to help you in your quest.

So while it’s fun to say I designed this house, in reality there is a huge team of people who took my ideas and made them real. The geotechnical consultant to prove the basement, the structural engineer to design the structural members, the MEP (Mechanical, Electrical, Plumbing) consultant to design the fresh air & HVAC systems, the solar firm to design the solar & storage systems, the cabinetry firm to design the kitchen, the low voltage consultant for ethernet drops, the drafting firm to create the construction documents, and of course — Brandon at Sierra Sustainable who wrangled all of these people and leveraged his extensive experience in building homes to transform my ideas from a concept into a comfortable, buildable, efficient house that meets code.

This house has been the top of my mind for a long time now, and I’m hoping to write more about how I’ve been thinking about it. I’ve long been frustrated with the shoddy houses built by recent generations — houses that are already falling apart and fail to inspire. But more importantly — our climate is changing — and our shelter is in desperate need of catching up. Floods, fires, thick smoke, extreme heat, ice storms, downpours, utility outages, and more — these are all going to be a regular part of our modern lives. We can’t rely on “typical” conditions going forward.

Building technology (both old and new) has answers to many of these challenges, and it doesn’t necessarily mean living in an underground bunker. Our homes can be resilient and comfortable if we so choose.