On the one hand, Earth is rapidly becoming uninhabitable for humans as a result of human-caused climate change. On the other hand, it’s pretty easy to ignore the cascading disaster most days. Climate change isn’t really a personal thing for most of us, especially if you live in North America or Western Europe. Sure — we have more wildfires, more droughts, more hurricanes, more floods, and a sort of ominous feeling of dread hanging over our heads — but it’s honestly not that big of a deal to crank up the air conditioner and book a flight to somewhere more comfortable.

But… what if you didn’t want to ignore it? What if you wanted to leave the world a better place carbon-wise than when you found it? You can’t do that with lifestyle changes unless you cease to exist. That’s why we talk about net zero approaches to carbon footprints — purchasing carbon offsets to balance out our emissions.

It’s a wonderfully simple idea.

Committing to net zero by purchasing carbon offsets is very easy and relatively cheap!

Step 1: Estimate Your Carbon Footprint

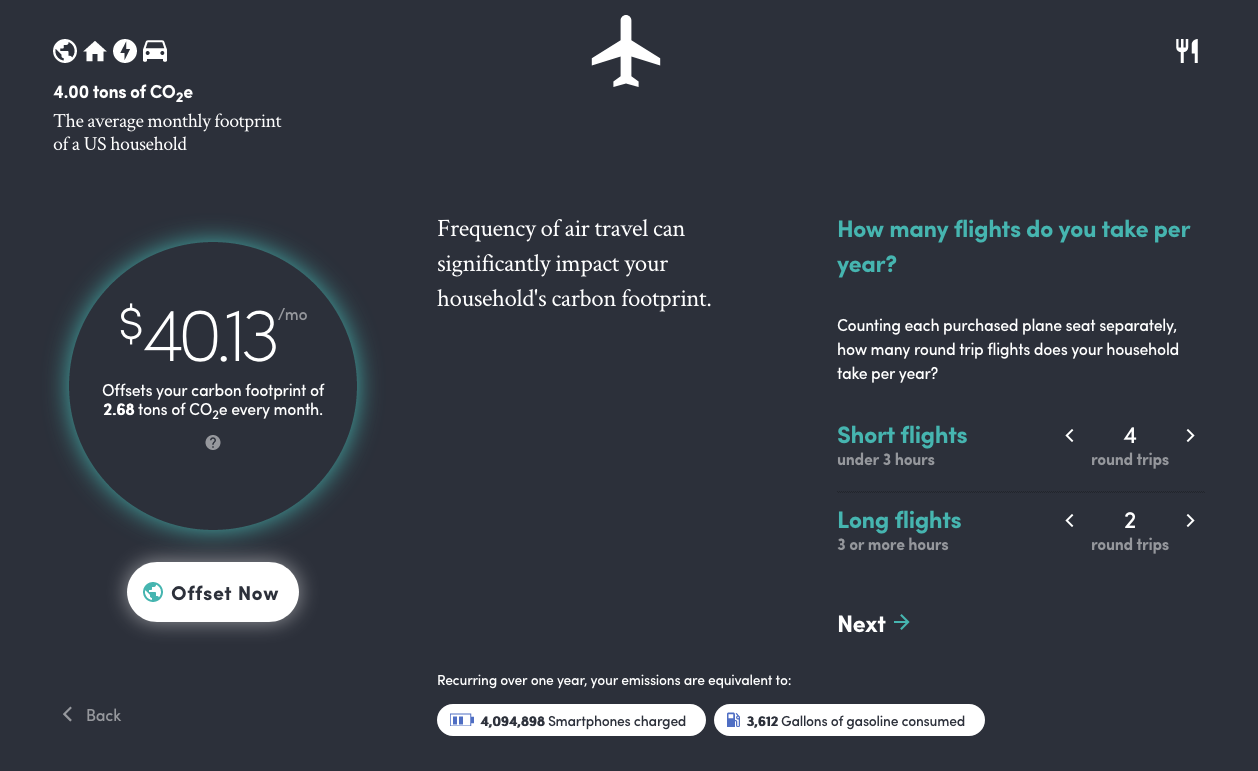

The average American’s footprint is roughly 2 tons per month, but you can always find a more detailed calculator tailored to your specific lifestyle habits. Tradewater’s calculator is a good example here. It estimates that my household (my wife & I) emit around 2.7 tons/mo.

Step 2: Purchase Offsets

I kind of already spoiled this step with the screenshot above. As you can see, you can purchase 2.7 tons of offsets from Tradewater for $40.13. Set up a recurring subscription with your credit card of choice and you’re done!

Here’s the thing. None of that is wrong but it definitely isn’t right either. Earnestly committing to net zero is incredibly complex, extremely expensive, and riddled with philosophical questions that cannot be universally answered.

Problem 1: Calculating A Carbon Footprint

While Tradewater’s calculator is a good tool to help understand how your lifestyle choices impact your carbon footprint (especially airplane flights!), it tends to leave out a lot of indirect emissions. When I eat meat it doesn’t cause emissions — the raising, processing, storing, and transportation of the meat does. That’s an indirect emission, and the only one they include. Now think about the indirect emissions for every Amazon box that gets delivered to your house. Every new thing you buy — every new car, light fixture, bottle of whiskey, and rug. Every dog, cat, and fish, and child you care for. Each has their own bundled emissions.

But what about things that will reduce emissions in the future — like solar panels, a new electric car, or better insulation for the house? What about the carbon-sequestering 2x4s that a carbon-emitting truck delivered?

What about the stocks I own? Am I responsible for that company’s emissions because I invest in them? If my company pays me to fly somewhere, am I responsible for those emissions or is the company? If I hire gardeners that use a gas leafblower on my property, are those emissions mine? Or should I only feel deep shame for ruining the lives of my neighbors?

And what about my lifetime emissions up to this point? Should I be responsible for my emissions since birth? My emissions in adulthood? Just the emissions from today forward? What about the emissions of my ancestors? If I inherited a house from my grandfather, who’s responsible for the emissions of constructing that house?

My Approach

I’ve settled on mostly ignoring calculators. By and large, an individual’s emissions scale with their income, not their choices. A billionaire vegetarian is going to be responsible for several orders of magnitude more emissions than an average earning carnivore. That being said, the EPA estimates the average American emits around 2 tons per month. Here’s my formula:

1 + [income factor] + [airplane factor] = monthly C02 in tons

This is imprecise, subjective, and by far feels the most correct. Do you believe your income puts you at about twice the level of consumption as a typical person? Maybe your income factor is 2. Do you only fly a couple times a year? Your airplane factor could be 1. Do you fly a private jet every month? Your airplane factor is probably closer to 10 or a 20.

Feel it out. I’m guessing my footprint lies between 1-10 tons/mo, and 4 tons/mo feels like a good guess. I spend a lot of money, but I also rarely fly and think about the carbon impact of my choices more often than not.

Now, how about lifetime emissions? There are some things I would definitely say I am responsible for — like the new house I’m building. That’s 100% on me. And since my goal here is to leave the world a better place carbon-wise than when I found it, I’m going to say I’m responsible for all my emissions since birth, understanding that I wasn’t wealthy until very recently.

75 tons/house × 1 house

+ (35 years × 2 tons/mo + 2 years × 4 tons/mo) × 12 mo/yr

= 1,111 tons

Final Answer: 1,011 tons + 4 tons/mo

Problem 2: Offsets Are Different Types of Negative

I’ve been using Tradewater as an example because they have a beautifully designed website, their offsets are pretty cheap, and because refrigerant management is a key strategy in winning our battle with carbon. But there is a big caveat here: Tradewater doesn’t technically remove carbon. They prevent potential carbon from being released — they avoid future emissions. This is much different than a company like Climeworks that deploys large machines that suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

Both of these are negative emissions, and any negative number cancels out a positive number. But I can’t convince myself that purchasing offsets from Tradewater for a flight I take tomorrow is a fair trade. It doesn’t actually feel like I’m offsetting my daily life. It feels a bit more like paying for past mistakes.

My Approach

For all of my future emissions, I want to purchase offsets from removal projects like Climeworks and Charm Industrial. That means 4 tons/mo + 75 tons/house. Any emissions I fail to offset from 1 year ago (when I started offsetting) forward get added to a one-time removal deficit.

For all of my past emissions, I want to purchase offsets from avoidance projects like Tradewater. That means paying down a historical debt of 864 tons.

Problem 3: Low Quality Offsets

The vast majority of offsets you can purchase today are extremely low quality. Does it involve a forest? It’s probably not actually removing any carbon. The good people at (carbon)plan have built a CDR (Carbon Dioxide Removal) Database that helps illustrate this. Quick — go filter by projects with the highest rating.

One result.

The quality of an offset is important! I don’t want to say the vast majority of the carbon removal industry is filled with hucksters and con artists… but if someone plants a tree, counts it as sequestering carbon for 100 years, then cuts down the sapling next year — did anything actually happen? No carbon got sequestered — but you sure got conned out of your money. Here are some questions to ask about a potential offset before purchasing it:

-

Does it remove carbon that otherwise wouldn’t have been released?

Capturing carbon from a natural gas plant isn’t better than just shutting down the plant. -

Is the carbon permanently sequestered?

Saving a rainforest today doesn’t stop someone from burning it down in the future. -

Does it create new emissions elsewhere?

Growing a tree for lumber sequesters carbon, but cutting it down and transporting it releases carbon.

I probably don’t need to tell you that high quality offset projects are far more costly than low quality projects.

My Approach

I want to purchase offsets from high quality projects, even if that means I am offsetting less than I am emitting.

Problem 4: This Isn’t An Industry Yet

I love Climeworks, but the process they use requires cheap geothermal energy and specific types of basalt bedrock to mineralize the carbon dioxide. In other words: it only works in a very small part of the world and can’t be scaled to anywhere near our current level of emissions. It’s also crazy expensive ($1000/ton)! Can you imagine the typical earning family adding a $2,000/mo bill for every household member? We can’t rely on Climeworks to offset the world’s emissions.

In order for net zero to be effective globally, carbon offsets need to be a mature industry with solutions that can be deployed cheaply all around the world. We aren’t there yet — any offsets you buy in 2021 are really kind of proof of concept. A bet on our future.

Part of why I subscribe to Climeworks is to offset carbon, but really I see myself as investing in their technology’s future.

My Approach

I want to purchase offsets from a portfolio of projects so that I can invest in many different carbon sequestration technologies because large-scale deployment relies on multiple methods of sequestering carbon.

Where I’m At

I’m not at net zero. I’m net zero ish. I’ve started. You can see a full breakdown over at my offset page where I’m going to try to keep a running total. Here’s the punchline as of today:

- I spend $1,500/mo

- I offset about 35% of my monthly emissions (removal)

- I have paid down 31% of my historical emissions (avoidance)

- I have a debt of 106 tons of one-time emissions (removal)

Why do I spend $1,500? Because I decided to give $500/mo to Climeworks about a year ago, then decided to continue that amount to other high quality projects I’ve found since then (Charm Industrial and Tradewater). Could I afford to spend more? Yes. If I had a typical income would I spend this much on carbon offsets? Absolutely not.

Why don’t I just pay for the offsets as I laid out above? It’s a good question. I hadn’t really given it much thought until I wrote this article. I probably should.

I dunno man! None of this stuff really benefits me. Another way of looking at this is that I set $1,500 on fire every month for no return. Then again, I’d love to live in a future where I can fly private and not feel like a shitheel.

And you know — isn’t that kind of the whole idea behind carbon offsets? If you are paying for high quality carbon removal equal to your emissions, I see no moral reason not to say you are actually living net zero. But maybe it’s also worth remembering that we don’t have great math for calculating our emissions, and offsets as they are priced today are only feasible for the ultra-wealthy.

The vast majority of the world isn’t even close to being able to pay for carbon offsets. They have no hopes of living net zero. And most of those people — especially those in the Global South — will suffer the most as the result of climate change. Maybe in that framework, net zero isn’t enough.

But don’t let that stop you from starting.